Beyond the Facade: 3D Printing and Anaplastology

Famed sci-fi author and philosopher Arthur C.Clarke once famously said that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is a beautiful, thought-provoking sentiment — although, we do have to remember that magic, as awe-inspiring as it can be, is also scary. For centuries, the supernatural has made people uncomfortable.

Case in point: Back when animation was primarily done on paper, without graphics processing units and animation programs running the show, cartoon characters were clearly recognizable as human, but they were also simultaneously and unambiguously nothing more than symbolic representations of humans. They were line-drawn characters with human voices, and though it requires suspension of disbelief to derive entertainment from animated media, it’s easy for the human mind to accept the connection.

Fast-forward to the present, and animators were introduced to computer-generated renderings and illustration. It was at that point that things began to feel kind of … weird. At first, the computer animation was sort of polygonal and angular — unpolished and unrefined. This was around the time that movies like Shrek began to surface and wow the world, pushing Pixar and Dreamworks into the international limelight for their award-winning animated works.

These movies were cute, and the people looked considerably more realistic. Nevertheless, they were still very much caricatures. However, as technology continued to advance and human representation via computer animation became more accurate, these anthropomorphic renderings became less cute and more creepy. This phenomenon is known colloquially as the “uncanny valley,” denoting the sensation of discomfort one experiences when the artificial approximation of a human being appears too much like the real thing.

With this in mind, it’s easy to understand why some of technology’s latest 3D printing applications might come off as “creepy.” Bradley University mentions that 3D printing is one of the top four new technologies that could positively impact healthcare. They write that this “process works by using a special kind of liquid or ‘ink’ that is comprised of human cells,” which is then “used by the printer to build the organ.” The hope is that someday this will replace the need for organ transplants and the risks associated.

Unfortunately, this 3D cell printing isn’t currently available for human use. Nevertheless, the healthcare field has been able to utilize 3D printing to help various people with prostheses, especially diminutive and finely crafted pieces. This equates to extremely realistic looking facial reconstruction — the caveat is that the more realistic these reconstructions are, the creepier they tend to look.

Anthropological Anaplastology

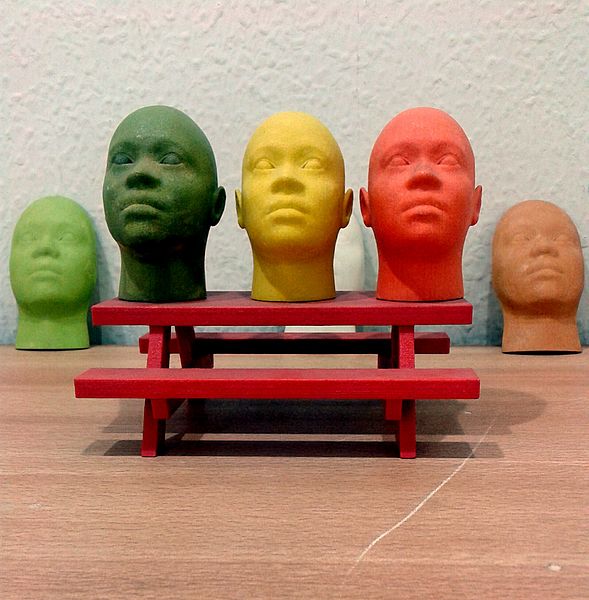

Anaplastology is the study and creation of artificial prosthetic parts (usually important, exposed ones) of the human body (mostly the face) for science and medicine. Anaplastologist Jan De Cubber’s facial reconstruction project employing a 3D printer reveals a far more realistic human face than the older papier-mache and/or clay models. The model itself is very lifelike, but the descent down into the uncanny valley feels real. It doesn’t help that the face has a large hole in it, or that someone is holding its “cover,” exposing the cold, lifeless metal skeleton beneath. It’s very H.P.-Lovecraft-meets-The-Terminator.

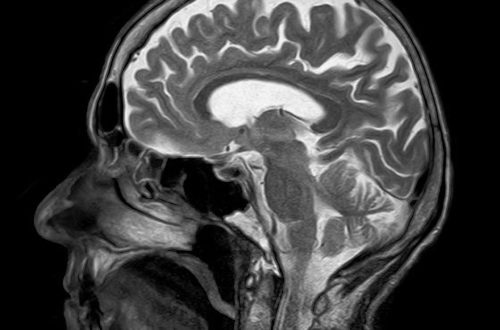

Sometimes anthropological facial construction is done to bring the past to life. 3D printing is used to fill out the skulls of historical figures and earlier human ancestors. Anthropological anaplastology (say that five times fast) has shown us what Neanderthals and Egyptian royalty looked like.

In Japan, some years ago, 3D printing and anthropological anaplastology collided to fight crime. The Japanese news agency ANN reported that the Tokyo PD had, based on an author’s sketch, mocked up a 3D model of the head of Katsuya Takahashi, the last remaining and un-jailed member of Aum Shinrikyo.

For those that don’t remember, Aum Shinrikyo is a terrorist organization that perpetrated the 1995 sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway system. The attack killed 13 commuters and sickened as many as 5,000. When the police raided Aum Shinrikyo’s compound, according to Wikipedia they discovered: “ … explosives, chemical weapons and biological warfare agents, such as anthrax and Ebola cultures, and a Russian Mil Mi-17 military helicopter.” Beyond that they also found manufactured firearms, millions of dollars in cash and gold, people imprisoned in compound cells, illicit sodium thiopental (“truth serum”), and methamphetamine and LSD labs.

Medical Anaplastology

Not all 3D printed anaplastology can truly be considered “creepy.” For example, below is a picture of cancer survivor Eric Moger and his wife. Moger has a 3D printed partial facial prosthesis for the part of his face that he lost to nose cancer in 2009.

“I was amazed at the way it looks,” said Moger to Telegraph.co.uk. “When I had it in my hand, it was like looking at myself in my hands. When I first put it up to my face, I couldn’t believe how good it looked,” he said.

“Before I used to have to hold my hand up to my jaw to keep my face still so I could talk properly and I would have liquid running out the side of my face if I tried to drink,” he continues. “When I had that first glass of water wearing the prosthetic face, nothing came out – it was amazing.”

Hopefully, in the future, we’ll be able to use sophisticated nanotechnology or even stem cells or biomimicry to re-grow our lost appendages. Until then, we’ll have to settle for 3D printing, which is, obviously, much more than most people take it for at face value (pun intended!). From anaplastology, to the manufacture of other odd medical devices like the heart sock, you can bet this technique will be improved upon and used for years to come.

All images used under CC BY-SA 3.0; Fist one by S. Zillayali; Second one by Half-pass; Third one by Cicero Moraes.

Would you like to receive similar articles by email?